USUI Mikao臼井甕男 (1865–1926) is celebrated as the founder of Reiki. While the story of his reception of reiki 霊気 (literally, “numinous energy”) is well-known, practitioners may be less aware of its resonance with Japan’s long history of mountain asceticism. Over a thousand years ago, religious itinerants began secluding themselves in the mountains in order to acquire special powers. Over time, these practices took shape as a self-conscious school known as Shugendō, which incorporated various schools of Buddhism, Daoism, and local beliefs associated with Shinto. A number of ritual manuals compiled by the ascetic Akyūbō Sokuden阿吸房即伝 (fl. c.1509–1558) in the early sixteenth century present the core philosophy and practices of Shugendō. If we consider Usui’s own miraculous experience in light of these texts, echoes of Shugendō come to the foreground.

Although the details of Usui’s experience in the mountains are sketchy, one popular version begins with a quest for personal awakening amidst a life of dissatisfaction. After being encouraged to “face his own death” by a Zen priest, Usui took to the mountains. At Mt. Kurama in the vicinity of Kyoto, he began an extended period of austerities, which included severe fasting. One night into the third week of practice, Usui was suddenly struck in chest by what felt like a massive thunderbolt. The blow was so powerful that it rendered him unconscious for several days. When he awoke, he was not only refreshed physically and mentally but felt that he had attained awakening. As he ecstatically descended the mountain, he stumbled and tore the nail off of one toe. It was only after cupping his toe and witnessing it miraculously heal that he became aware of the power that he had received in the mountains.

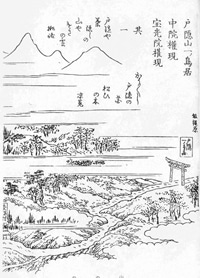

Laying aside the question of historical accuracy, let us consider its resonance with attitudes and practices concerning Japan’s numinous mountains. First of all, Usui’s choice of Mt. Kurama for his ascetic practice (shugyō 修行) is unlikely a coincidence. For centuries, adherents of Shugendō secluded themselves at this mountain in order to practice severe forms of fasting, chants under waterfalls, and ritualized hikes. In other words, the site has long been regarded as a reizan, or “numinous mountain”—a term which incorporates the same character (rei 霊) as Reiki.

Usui’s incident at Kurama furthermore, shares many traits with pivotal transformations experienced by Japan’s famous itinerants and founders of religious schools. In a text titled Essential and Key Secret Teachings of Shugen Practice, Sokuden describes the awakening experience of En no gyōja, the alleged founder of Shugendō:

Our lofty founder, En the itinerant, experienced the inner realization of the original awakening of [the Buddha] Vairocana here. From faraway he walked to this mountain range and practiced the secret method of sudden awakening in this very body (sokushintongo 頓悟即身). He externally based himself on the sovereign seal of the bodhisattva, Nāgârjuna, in order to divine its trace from afar to this mountain. Through this effort, he magnificently spread the mysterious teachings of the “opened stūpa” of India. How virtuous was his unification of the exoteric and esoteric practices and the mysterious concordance between the two laws of phenomena (ji 事) and principle (ri 理)! How valuable are his secret methods among all methods and his transmitted innermost secrets among the most profound secrets!

This account appears eight centuries after En’s time and should be understood as encompassing the ideals of sixteenth century Shugendō rather than an accurate portrayal of En’s biography. And while some of the language here alludes to the rather obscure field of medieval Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō), the similarities between the stories of the two founders are clear: a profound awakening inside the mountains, a physically transformative experience, and the exclusive transmission of encoded, secret methods of practice. Despite this aura of secrecy, once this transmission is delivered, success to anyone is available, as the text elaborates:

Fellows have entered this peak in ordinary bodies unaltered from the lowest level of superficiality. Without delay, they climbed to the eight-petaled platform of the center of the Womb [Realm maṇḍala]. Stepping on to this ground in untransformed bodies produced by a father and mother, they fully realized the indestructible Dharma body [of Vairocana] of the Diamond [Realm maṇḍala]… As a path that is simple to cultivate and easy to realize, nothing exceeds the practice of Peak Entry (nyūbu入峯). Truly, both phenomena and principle are mysterious, one’s inner realization is non-dualistic (funi 不二), and this marvelous practice constitutes the one mind.

The Womb and Diamond realms mentioned here were viewed as coupled maṇḍalas that were overlaid on to mountain ranges around the country. The practice of “entering such mountains” (nyūbu入峯) and conducting the proper course of austere rituals allowed the practitioner to awaken and nurture special powers. Like these earlier ascetics, Usui may have also felt that his awakening and power came as the result of hard practice.

…

Another element in Usui’s story is his encounter with a priest of Zen Buddhism, which has long been connected with mountains and the school of Shugendō. As such, the advice of this Zen master to “face death” (or stated more literally as, “Why not check out death once?”) alludes to mountain asceticism. Sokuden’s Secret Record of Regulations for the Transmissions of the Three Peaks addresses this theme directly:

Discarding the body in order to pursuing awakening encompasses both practice (ji 事) and theory (ri 理). First, the practice of discarding the body in order to pursuing awakening neither shirks the precipitous dangers of high mountains and deep ravines nor laments the two roots of the body and life. For this reason, it constitutes the exclusive pursuit of the Buddhist path. Second, the theory itself consists of the untransformed five words, discard + one’s + body + pursue + awakening. They exist entirety as the immediate essence of physical transformation into a buddha (sokushin sokubutsu 即身即仏). Our lineage places the most emphasis on this.

Though the language here is somewhat cryptic, the notion here of discarding one’s body in order to pursue awakening directly corresponds with Usui’s experience. Like the advice to “face death” by Usui’s master, the implication in this passage should not be confused with suicide. Instead, it refers to a willingness to completely let go of oneself—mentally and physically—in the mountains in order to achieve awakening.

…

Finally, one closing passage from Sokuden that is worthy of reflection in terms of both Reiki and society reads,

May we enter into the Buddha land of the letter “A” (i.e., the mountains) with our extended families, our fathers and mothers of many generations, nine generations of ancestors, those to whom we are indebted for generations, patrons [of the Buddhist community], all connected living beings, the myriad spirits of the three realms, enemies and friends, those both noble and vulgar, those of the six destinies and four [types of] birth, those with and without connections [to the Dharma], the entire realm of devils, all gods and demons, those already deceased and those who will die after us, all that exhausts the Dharma realm, and sentient beings of water and land. All rely on the grasses and are connected to the trees. It is into this Buddha land of “A” that we bring ourselves and others.

This last paragraph of the text may have been performed as a chant and thus some of the emphasis lies in the rhythmic quality of these various classifications. Despite their redundancy at times, the repetition also hammers home a decisively holistic vision of the world, in which all beings—visible and invisible—are closely connected to one another. This understanding of interconnectedness among all forms of life is in fact, characteristic of many Buddhist schools throughout East Asia. By relying on the powers that reside in the “grasses” and “trees” of the mountains, one can pursue awakening and realize the idea of shared existence among all beings. Perhaps it is this same sense of unity that inspired Usui and many of his students later to share the practice of Reiki.

Passages in this essay, unless stated otherwise, are translated from the Shugen shūyō hiketsu shū 修験修要秘訣集 (Essential and key secret teachings of shugen practice). Ca. 1524–1558. In Shugendō shōso修験道章疏 (Collection of Shugendō works). Vol. 2: 365–409. Tokyo: Kokusho kankōkai, 2000 reprint [1921].

Sanbu sōjō hōsoku mikki 三峰相承法則密記. Ca. 1521–1524. In Shugendō shōso 2, 488b–489a .

Caleb S. Carter, Ph.D. Candidate

Asian Languages & Cultures, UCLA

2011-2012 Japan Foundation Fellow

Keio University, Tokyo

blog: asceticsandpilgrims.wordpress.com/

Comments 5

Hi Caleb,

Thanks for writing this excellent article.

What is interesting to note is that these words, see below, appear on Usui’s memorial stone, which indicates he did a lot of practice and that the development of Reiki, finding our true self, doesn’t come easy.

Shuyo renma

shuyo 修養= cultivate one’s mind, be trained in self-discipline

renma 練磨= exercise

tanren 鍛練= anneal; temper

kushu shinren=shinren kushu 辛練苦修= master something through a bitter experience article.

Cheers

Frans

Here are some other articles on our website, which link in with Caleb’s article.

http://www.ihreiki.com/blog/article/researching_reiki_training_from_a_japanese_viewpoint/

http://www.ihreiki.com/blog/article/shugendo_and_the_system_of_reiki/

http://www.ihreiki.com/blog/article/what_i_am_discovering_from_my_japanese_shugendo_training_about_reiki/

http://www.ihreiki.com/blog/article/sutras_and_the_system_of_reiki/

What is really striking is how similar the Shugendo experience of the mountain quest is to the traditional Native American vision quest. I’ll bet traditional peoples the world over followed similar practices in order to receive vision/self-knowledge/wisdom and bring their transformative experience back to share with their people. What a shame today’s societies don’t embrace this practice!

Thanks, Frans! Looks like an interesting tombstone. I’ll have to check it out while I’m in Tokyo.

Elly, insightful comment. I’ve wondered about similarities between Shugendo and Native American attitudes toward the natural environment. As for shamanistic practices within Shugendo, there are definitely similarities with many other parts of the world.

Hi Caleb,

It is written in old Japanese but definitely interesting.

Going to the mountains is also a very Taoist practice and the yogi’s in the Himalaya do the same thing. I think the universal truth can not be hidden.